- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Youth

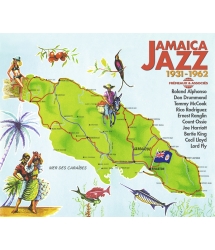

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

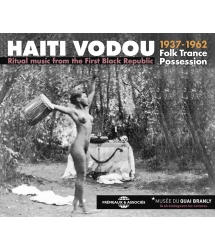

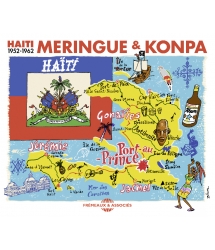

- West Indies

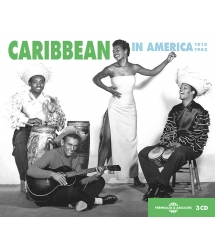

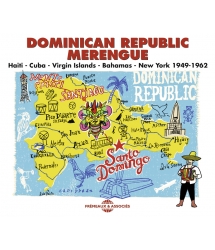

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Africa

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - O.S.T.

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

My Shopping Cart

Total (tax incl.)

€0.00

Subtotal

Free

Shipping

Total product(s)

0 items

Shipping

Free

The leading publisher of musical heritage and the Sound Library

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- History of Philosophy (PUF)

- Counter-History and Brief Encyclopedia by Michel Onfray

- The philosophical work explained by Luc Ferry

- Ancient thought

- Philosophers of the 20th century and today

- Thinkers of yesterday as seen by the philosophers of today

- Historical philosophical texts interpreted by great actors

- History

- Social science

- Historical words

- Audiobooks & Literature

- Youth

- Jazz

- Blues

- Rock - Country - Cajun

- French song

- World music

- France

- Québec / Canada

- Hawaï

- West Indies

- Caribbean

- Cuba & Afro-cubain

- Mexico

- South America

- Tango

- Brazil

- Tzigane / Gypsy

- Fado / Portugal

- Flamenco / Spain

- Yiddish / Israel

- China

- Tibet / Nepal

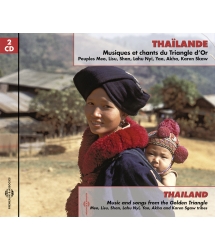

- Asia

- Indian Ocean / Madagascar

- Japan

- Africa

- Indonesia

- Oceania

- India

- Bangladesh

- USSR / Communist songs

- World music / Miscellaneous

- Classical music

- Composers - O.S.T.

- Sounds of nature

- Our Catalog

- Philosophy

- News

- How to order ?

- Receive the catalog

- Manifesto

- Dictionnary

Asia

Asia